Tired of feeling passive, and yearning to get closer to nature, Martyn Roberts swapped safari holidays for expeditions – and learned as much about himself as he did about wildlife.

Martyn Roberts never forgot his first safari in South Africa – it left him wanting more. He loved the thrill of being close to wildlife — but as he put it, ‘I wanted to get hands-on. I wanted to make a difference, to do something more demanding that allowed me to express these beliefs, ideas and interests.’ Those hopes lingered until 2002, when a chance encounter led him to Biosphere Expeditions and a life-changing trip to Namibia.

At the time, Martyn had just come out of his first marriage and was ready for something new, something bold. His earlier safari was too short, too passive. So when he discovered Biosphere Expeditions and heard about an upcoming two-week project in Namibia, he took a leap of faith. ‘I wouldn’t call it the hard sell,’ Martyn says as he recalls his first conversation with Matthias, the expedition leader, ‘but he insisted that I join. It was an encounter with the unknown.’

For Martyn — who had always travelled with friends, family or a partner — heading off by himself to find the meeting point in Windhoek felt like a huge step. ‘Yes, it was the first time I’d travelled on my own,” he remembered. ‘I wasn’t overly worried, but I was apprehensive. What would it involve? It was a leap into the unknown.’

What he found in Namibia wasn’t at all what he’d expected. ‘The country itselt … just how wild and desolate it was,’ he marvels. ‘So much bigger than I expected. The cheetah was the species we worked with – I was a bit surprised how well it all ran!’ He still laughs about his first meeting with another big beast: Matthias, in a Windhoek café, when Martyn realised his expedition leader was nothing like the ‘old man with a big beard’ he’d imagined.

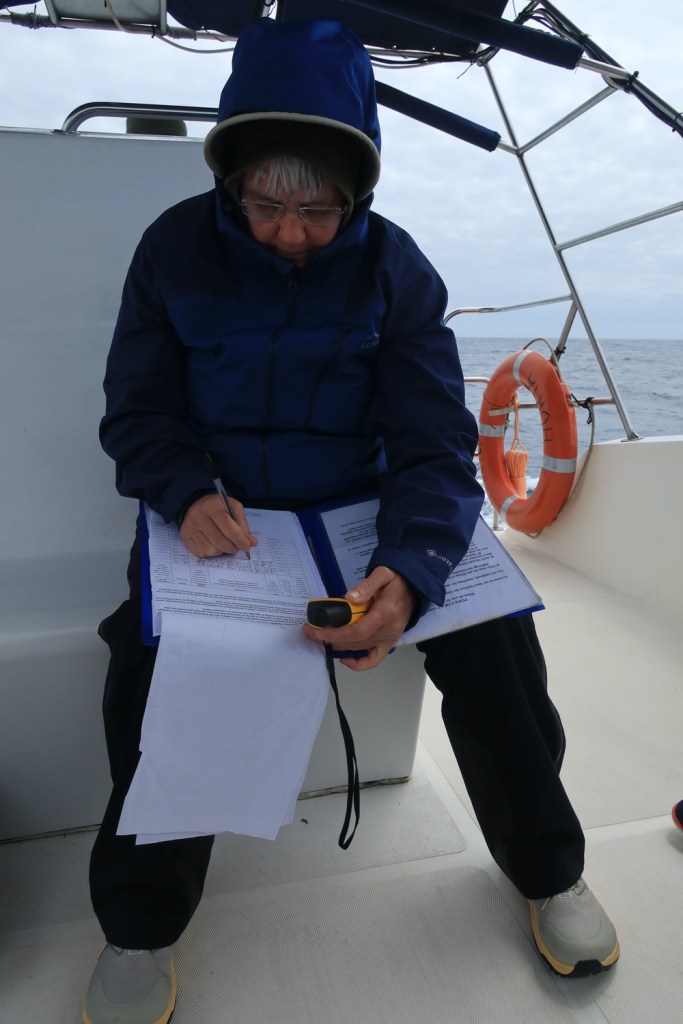

Gruelling hours, hard physical work and pushing comfort zones: Martyn discovered much more than animals alone. He and his team had to maintain vehicles, drive out into remote areas, check camera traps, and spend hours in hides. ‘Everyone was silent when Matthias asked who wanted to drive,’ Martyn says. ‘I stuck my hand up and said, ‘I’ll give it a go,’ driving people I’d never met, hours out of town, in a foreign country, at times when you’re tired can be challenging. But you do it.’

That first two-week expedition changed the course of Martyn’s life. He kept returning: Altai, Sumatra, Brazil, drawn back again and again. ‘As each expedition happened, you could sense a change,’ he explains. ‘I thought, ‘I like this. This is good. We’re giving a lot and getting a lot.’ And you could feel no one wanted to leave.’ Simply deciding to go – and accepting responsibility for getting himself to the rendezvous point, no matter how remote – was a challenge in its own right. But he relished it. ‘It’s the first test to see if you’re independent and can take responsibility.’

Of all the expedition he’s been on taken, Sumatra in 2015 stands out as a defining moment. Heat, humidity, dense jungles, the exhaustion of wading through waterlogged terrain – it tested him like nothing else. ‘We had base camps with WWF, rats in the night, someone set up a camera so we got rat TV every morning,’ he chuckles. ‘But the expedition work was seriously challenging. I approached the expedition leader talking about quitting – I was in my late 50s and finding it tough. A couple of days I didn’t go out because it was too hard, and I felt I was holding the group back. But I got back in the end!’ It’s a point of pride that he persevered. ‘Even with Wellington boots, boggy ground, up and down, thigh-deep in water … it was unpleasant. But I managed,’ he says. ‘It’s addictive. Can’t get there from here? You can, you can, because you’re part of a team.’

Returning home after each of these experiences has been its own kind of challenge. ‘It’s a bit like the post-holiday blues,’ Martyn admits. He’d come back buzzing with stories: Muddy boots, extraordinary wildlife encounters—but maintaining his passion at home wasn’t easy. Still, that energy proved infectious for friends who saw just how transformative the expeditions had been for him.

In time, Martyn also realised that his once ‘rose-tinted view’ of wildlife charities had grown more nuanced. “Before expeditions, I supported charities like WWF. You think everything runs smoothly. But then when you do it yourself, helping professionals, you realise how difficult it is, how many challenges you face — it’s not as easy as you might think,’ he muses. The fieldwork – hauling camera traps, trekking through punishing environments, collecting data – deepened his respect for conservationists. ‘I do it two weeks a year, and it’s made me realise money isn’t everything. Commitment, courage, consistency: that’s critical,’ he says.

Martyn’s convictions haven’t dimmed; they’ve evolved. His adventures have taken him across continents, from desert scrubs to humid jungles, always in search of something more meaningful than a fleeting holiday. Each expedition tested him in a new way. Each time, he rose to the challenge. Now, he can’t imagine who he’d be without those experiences – or the confidence they’ve given him. ‘For some people, this might be a one-off. But I realised I relish it,’ he says, bright-eyed with the memory. ‘It’s rare in life. You give a lot, but you get a lot back, and that changes you.’